Advanced Intelligence Analysis: The Way Forward (Especially for the Developing Countries)

In today’s environment, national security threats rarely appear without warning; they evolve gradually through shifts in intent, capability, and perception. What defines today’s environment is not increased uncertainty, but the speed with which misjudgments become strategic losses. This series advances a central claim: intelligence advantage now does not lie mainly in how much information is accumulated, but in the disciplined structuring of uncertainty and timely action. The methods discussed are well-established and scientific; what has changed is the intensity of the global threat landscape and the rising cost of analytic delay. In previous postings, we examined how Bayesian knowledge elicitation enables rigorous reasoning even in the absence of data, and how such methods were already mature by 2018. The obvious next question is not whether these tools work, but who uses them—and who does not. This part confronts this question directly, focusing on Africa and other developing regions that remain largely excluded from advanced intelligence decision science.

INTELLIGENCEGENERAL TOPICSNATIONAL SECURITYSOCIAL COMMENTARYSCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY

Structural constraints and missed opportunities

For Africa and its leadership, it is not difficult to appreciate why highly sophisticated decision-support and intelligence systems have not yet been fully integrated into national governance and security architectures. These systems demand advanced technical expertise, sustained institutional capacity, and supporting technologies that may not be immediately accessible or familiar. That said, it remains a matter of concern that in many instances, even modest or foundational decision-support frameworks have struggled to gain acceptance—despite their potential relevance to national stability and, in some cases, political continuity itself.

Across discussions with multiple participants during the Knowledge Elicitation & Reasoning with Bayesian Networks for Policy Analysis workshop, a consistent observation emerged: Africa has largely remained peripheral to these developments, while external actors—whether competitors, partners, or adversaries—have become increasingly proficient in applying advanced analytical systems to anticipate and shape events on the continent.

Early warnings and national case experiences

Nigeria

In Nigeria, during the administration of former President Goodluck Jonathan, a range of intelligence and decision-support models were proposed. These would have addressed issues such as foreign economic espionage, internal sabotage and corruption, evolving internal security threats, the protection of senior public officials, the diminishing operational effectiveness of the military, and other matters of national significance. The intent of these models was not alarmist, but preventative—aimed at offering early warning and strategic options in an increasingly complex security environment. But the proposal did not see the light of day. It was stifled by bureaucracy and absence of political connection—the president never got to see the proposals.

What were the costs?

Under Goodluck Jonathan, the immediate price was loss of political power. The administration entered the 2015 election cycle with growing internal security strain, elite fragmentation, economic vulnerability, and declining confidence in state capacity—dynamics that predictive and probabilistic models are specifically designed to surface early.

The longer-term costs were institutional:

Loss of incumbency advantage in a sitting-government defeat

Erosion of public trust in state security and governance

Expanded space for criminal and insurgent actors

Increased fiscal and human costs of delayed security response

While the transition itself was peaceful, the regime paid through strategic surprise, loss of control over narrative and timing, and diminished state leverage at a critical juncture.

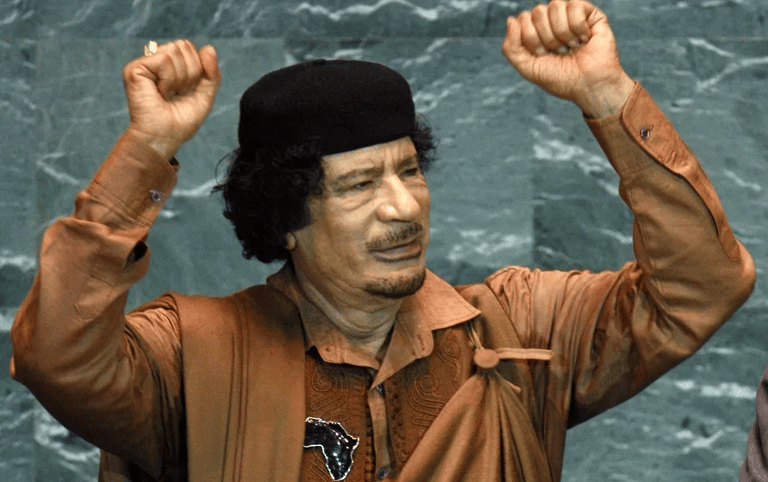

Libya

Similarly, in Libya under the leadership of Colonel Muamar Gadhafi, analytical models suggested the urgent need for proactive strategies to mitigate emerging risks to the regime, the state, and the wider subregion. This was before the Arab Spring (2010-2012); at a time when most people could not see the enormous danger that was already building, when Libya appeared to be reintegrating into the global community, with its leader visibly engaged on the international stage. The prevailing confidence of the administration of Colonel Muamar Gadhafi, however, left little room for the consideration of such vulnerabilities, and the consequences unfolded with striking speed.

What were the costs?

For Colonel Muamar Gadhafi, the price was total regime collapse. Again, early-warning models pointed to converging internal dissent, external intervention risk, and elite defection at a time when the regime believed international reintegration had reduced existential threats.

The costs were absolute:

Violent overthrow of the state

Disintegration of national institutions

Loss of territorial control

Prolonged civil conflict and regional destabilization

The leader’s own death

Here, the failure to treat vulnerability as analytically real—rather than politically inconvenient—translated into irreversible strategic loss within months.

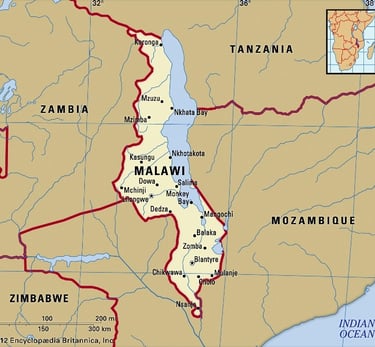

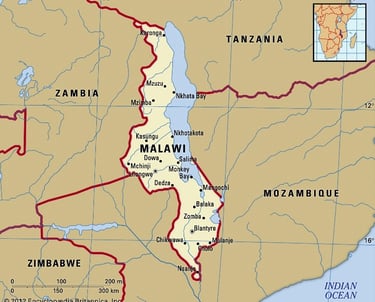

Malawi

In Malawi, during the latter period of President Bingu wa Mutharika’s tenure and the emergence of Arthur Peter Mutharika as a leading political figure, models pointed toward a difficult and abrupt political transition. The analyses suggested that significant change was imminent, and that the political landscape would shift in ways that would be challenging for those closely associated with the outgoing administration.

What were the costs?

In Malawi, the price was political disruption rather than state collapse.

Analytical models anticipated:

A sudden leadership vacuum

Institutional stress during succession

Reduced viability of continuity candidates

The costs included:

Abrupt transition shocks

Weakening of regime continuity

Heightened political contestation

Short-term erosion of policy coherence

This case demonstrated that even without a violent breakdown, ignoring foresight imposes avoidable instability and loss of preparedness.

Leadership mindsets and resistance to analytical tools

Taken together, these cases illustrate the serious national and personal consequences that can arise when emerging risks are insufficiently anticipated. More broadly, many African leaders—operating within strategic frameworks shaped by earlier historical periods—have found it difficult to adapt to a global environment that is now deeply interconnected, fast-moving, and increasingly driven by data, computation, and probabilistic reasoning. Resistance to advanced decision science tools often stems not from hostility, but from unfamiliarity, skepticism, or discomfort with methodologies that are not immediately intuitive.

An observation by a U.S. Air Force Captain affiliated with the Defense Intelligence College in Washington, D.C., who had extensive experience applying Bayesian analytical methods to threat prediction, offers some insight into this resistance:

“Due to the highly mathematical nature of Bayesian Decision Analysis, many potential users will feel uneasy trusting the resulting assessments.”

The case for probabilistic reasoning under uncertainty

At the same time, scholars such as Dr. Aidan Feeney and Dr. Evan Heit have articulated a strong case for such approaches. In their discussion of Inductive Reasoning: Experimental, Developmental and Computational Approaches, they emphasize that:

“Bayesian inference is important because it provides a normative and general-purpose procedure for reasoning under uncertainty.”

Africa, like many regions of the world, faces profound and layered uncertainties—political, economic, and security-related. Elsewhere, governments have increasingly turned to advanced mathematical and computational models to anticipate destabilizing scenarios, reduce their likelihood, or mitigate their impact. In contrast, a number of African leaders continue to rely heavily on intuition, precedent, or personal judgment, even as powerful external actors employ sophisticated analytical tools that allow them to forecast—or in some cases influence—outcomes on the continent.

Consequences of strategic imbalance

The consequences of this imbalance have been severe: substantial loss of life, depletion of national and private resources, gains by criminal and subversive networks, and repeated strain on military and security institutions. In several cases, leaders themselves have borne the ultimate cost of miscalculation, losing power, legitimacy, or personal security, while their countries have descended into deeper economic and security crises.

Practical pathways toward capability development

At a foundational level, however, meaningful progress is achievable. African states can begin by investing in data warehousing, distributed databases, and adaptive signals-intelligence systems. While it would be unrealistic to expect the development of entirely new, capital-intensive technologies, existing cloud-based platforms have significantly lowered the barriers to entry and democratized access to advanced capabilities.

National security cannot be imported!

Crucially, these initiatives should be locally driven. Overreliance on external consultants or expatriate expertise has frequently introduced competing interests and long-term dependencies. With appropriate capacity building, predictive analytics could have signaled vulnerabilities in administrations that appeared politically secure.

Strategic value of stochastic and predictive models

Stochastic modeling, computational analytics, and intelligence fusion offer tangible benefits in anticipating, tracking, and disrupting security threats. By estimating probability distributions of possible outcomes and incorporating random variation over time—based on historical data and time-series analysis—such models can help forecast adversarial behavior. This, in turn, increases the risks faced by hostile actors while enabling governments to deploy scarce resources—financial, military, and human—with greater precision and effectiveness, ultimately preserving lives and property.

My concluding perspective

In a world defined by uncertainty, the careful adoption of advanced decision-support tools is not a luxury, but an increasingly essential component of responsible governance. The challenge for African states is not merely technological, but institutional and cultural—requiring a gradual but deliberate shift toward evidence-based, anticipatory decision-making that aligns with the realities of a complex global system.