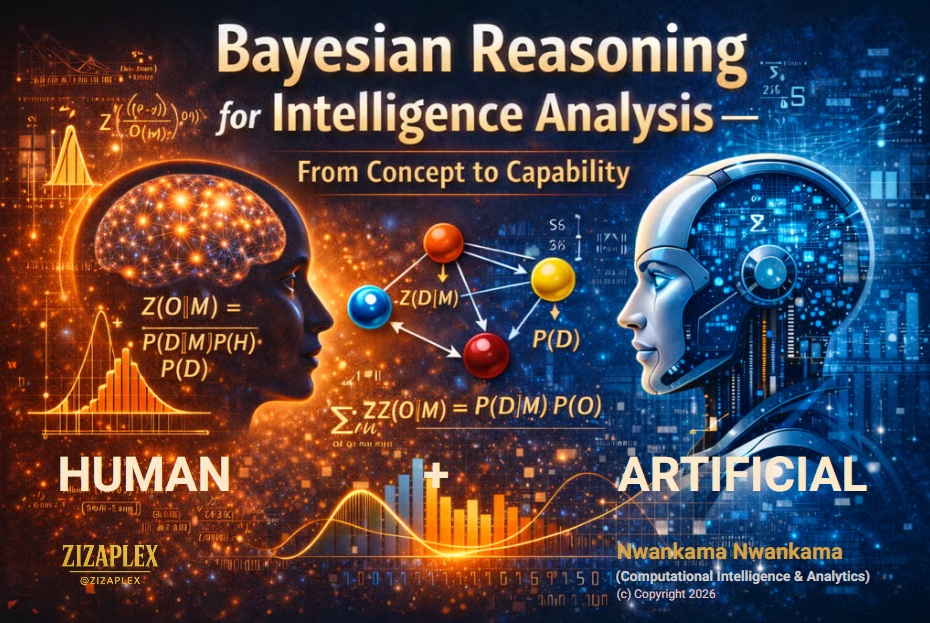

Bayesian Reasoning for Intelligence Analysis — From Concept to Capability

In an era of accelerating geopolitical uncertainty, intelligence analysis must contend with complex, rapidly evolving threats that often emerge beyond national borders. Bayesian reasoning offers a powerful framework for navigating such conditions, particularly when data are limited or unreliable. While its viability was already evident by 2018, this article examines what has changed since then—and how those changes enable operational intelligence capabilities today.

INTELLIGENCENATIONAL SECURITYGENERAL TOPICSSOCIAL COMMENTARYSCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY

The 2018 Workshop and Its Analytical Foundations

In December 2018, I was invited to participate in the Workshop on Knowledge Elicitation and Reasoning with Bayesian Networks for Policy Analysis, held at the Virginia Tech Applied Research Center in Arlington, Virginia. The workshop brought together a diverse group of practitioners and researchers, including intelligence analysts, military and strategic intelligence officers, policy and strategy analysts, knowledge managers, risk analysts, decision scientists, operations research analysts, counterterrorism specialists, and modeling and simulation experts. Participants came from the United States, France, and Israel.

The central objective of the workshop was to demonstrate how structured human expertise could be elicited and transformed into high-dimensional computational models of complex problem domains using Bayesian networks. Through guided exercises, participants collectively constructed models that captured causal relationships, uncertainties, and competing hypotheses relevant to geopolitical and security scenarios.

While some of the tools and systems discussed were relatively new, the underlying principles were not. The use of mathematical and computational models to assess geopolitical risk and support decision-making has a long history. What distinguished the approach showcased at the workshop—particularly through the Bayesia Expert Knowledge Elicitation Environment (BEKEE)—was the ability to reason formally and quantitatively even in the absence of reliable numerical data.

A key insight was that meaningful and actionable predictions could be generated by systematically eliciting expert judgment, encoding causal knowledge, and preserving uncertainty within a probabilistic framework. During the workshop, while discussing with some participants, I also highlighted underexamined cases from Africa, including Nigeria, Libya, and Malawi, to illustrate how such methods could be applied in contexts where data scarcity and institutional constraints are especially pronounced. These cases will be revisited later in this discussion.

The practical applications explored at the workshop focused largely on military mission planning, but they extended naturally to executive security, insurgency analysis, counterterrorism, espionage detection and mitigation, and broader policy formulation. Across these domains, BEKEE served as the primary platform for eliciting, aggregating, and modeling expert knowledge.

What Was Demonstrated in 2018: Science That Goes Beyond Data

By 2018, the discourse around intelligence and analytics was already heavily influenced by the rise of “Big Data.” Popular narratives often suggested that truth, rigor, and scientific validity could only be achieved through large volumes of empirical data. Phrases such as “In God we trust; all others must bring data” reinforced the perception that decision-making without data was inherently flawed.

This view, however, reflects a fundamental misunderstanding. Advances in Bayesian and stochastic modeling, combined with formal methods for representing human reasoning, have made it possible to support reliable decision-making even when data are limited, unreliable, or entirely absent. In many geopolitical and security contexts, waiting for sufficient data is not an option.

Humans possess substantial knowledge about conflicts and risks—some explicit, some tacit; some qualitative, some quantitative. This knowledge includes assessments of intent, capability, causality, and context that data alone cannot provide. While data can reveal correlations, frequencies, and patterns, it is inherently limited to what has been observed, measured, and encoded. Human judgment, by contrast, can reason beyond the available evidence, drawing on experience, theory, analogy, and counterfactual thinking.

One critical dimension that data by itself cannot uncover is causality: understanding how and why certain factors influence others, even when direct empirical relationships are difficult or impossible to observe. Causal reasoning often depends on mental models—implicit theories about how systems work—rather than on statistical regularities alone. For example, in conflict analysis, humans routinely infer intentions from incomplete signals, anticipate second- and third-order effects, and assess how actors might adapt once conditions change. These inferences rely on structured imagination and contextual understanding, not merely on historical data.

Moreover, many of the most consequential risks are rare, novel, or strategically concealed. In such cases, relevant data may be sparse, misleading, or deliberately manipulated. Humans can still reason about these situations by integrating domain knowledge, historical analogies, ethical considerations, and an understanding of incentives and constraints. This allows them to form causal explanations and plausible scenarios even in the absence of strong empirical validation.

In short, data is indispensable for grounding analysis, but it is insufficient for explaining the mechanisms that drive behavior and outcomes. Causality emerges not simply from observing what happens, but from interpreting why it happens—a process that depends on human judgment, conceptual frameworks, and the ability to reason under uncertainty.

We saw that, using BEKEE, it was possible to elicit this causal knowledge from subject-matter experts and encode it into Bayesian network models. These models enabled the simulation of potential interventions and the exploration of alternative policy responses while explicitly accounting for uncertainty.

The Wisdom of Crowds in Complex Analysis

As expected, no single expert at the workshop possessed comprehensive knowledge of the full range of issues embedded in the case studies. However, many participants held deep expertise in specific aspects of the conflicts under examination. Rather than seeking a single authoritative perspective, the analytical approach deliberately decomposed complex problems into smaller, more tractable components.

This design would allow individual experts to contribute where their knowledge was strongest. The objective was to capture a diverse range of perspectives and causal assumptions, and then integrate them into a unified probabilistic model. In this sense, the process would draw on the principle of the wisdom of crowds, where aggregated independent judgments often outperform isolated expert opinions.

Historically, similar objectives motivated the development of the Delphi Method during the early Cold War, notably at the RAND Corporation. While effective in principle, the Delphi Method was slow and cumbersome, relying on repeated rounds of questionnaires distributed and collected manually.

Reinventing Delphi: Real-Time Knowledge Elicitation with BEKEE

As presented, BEKEE can be understood as a modern, computational reinvention of the Delphi Method. The Delphi Method was developed in the early 1950s at the RAND Corporation. It was created by Olaf Helmer, a German-American philosopher, mathematician, and futurist, and Norman Dalkey, an American mathematician and research analyst. The method was originally intended to support systematic forecasting and military planning. It is a structured process for eliciting expert judgment through iterative rounds of anonymous input and feedback. This design helps reduce bias and encourages convergence toward an informed consensus. BEKEE serves the same purpose of eliciting and refining expert judgment, but it does so in real time through a web-based interface that participants can access on their own devices.

At the workshop, we could see how BEKEE enabled the systematic collection of expert opinions, the explicit representation of uncertainty, and the encoding of causal relationships into a shared Bayesian network. Although individual judgments were imperfect, their structured aggregation is what would produce a surprisingly robust approximation of the underlying problem domain. The resulting models would provide a common analytical framework for discussing policy options and evaluating their potential consequences.

Reasoning Under Uncertainty

A final and critical theme of the 2018 discussion was the proper treatment of uncertainty. Bayesian network models allow analysts to preserve uncertainty rather than suppress it. This avoids two common analytical failures: the false precision of single-point estimates and the opposite extreme of abandoning quantitative reasoning altogether due to uncertainty.

By explicitly representing uncertainty arising from diverse expert opinions, Bayesian models support probabilistic inference and scenario analysis. On the basis of the constructed networks, participants were able to explore the implications of different interventions and simulate the likely outcomes of alternative policies—demonstrating, even in 2018, that Bayesian reasoning was already a powerful and practical tool for intelligence analysis.

Where We Are Today

We have witnessed a spectacular maturing of the ecosystem.

Since 2018, group elicitation methods have become more structured and operationally friendly. End-to-end platforms now integrate training, facilitation, elicitation, modeling, and scenario analysis into a single workflow. These advances reduce dependence on artisanal expertise and make Bayesian reasoning more institutional and repeatable.

Equally important are new protocols designed for classified and sensitive environments, where data sharing is constrained. Bayesian models increasingly function as a secure translation layer between raw intelligence and decision-making, allowing insights to be shared without exposing sources or methods.

Time, dynamics, and hybridization

Intelligence problems are rarely static, and this reality has driven the wider adoption of Dynamic Bayesian Networks (DBNs), which explicitly model how conditions evolve over time. These are particularly valuable for tracking insurgencies, political instability, and regime risk—domains central to the African cases discussed earlier.

In parallel, Bayesian networks are now routinely combined with machine learning techniques in data-rich domains such as cyber intelligence. This hybrid approach allows developing countries to extract value from uneven datasets while preserving causal interpretability.

Finally, the tooling ecosystem itself has matured. Clearer maps of available BN software reduce vendor lock-in risks and allow constrained governments to assemble affordable, sovereign analytic stacks.

Concluding Thoughts

The most significant development since 2018 is not any single tool or technique, but the realization that advanced intelligence analysis must be institutionalized, not improvised. Even having capabilities like B-ISAC is not a software purchase; it is a disciplined way of thinking embedded in people, processes, and governance.

For developing countries, the choice is stark. They can continue to operate in a world shaped by the probabilistic foresight of others, or they can claim analytic agency over their own futures. Bayesian reasoning does not guarantee success—but refusing it all but guarantees surprise.